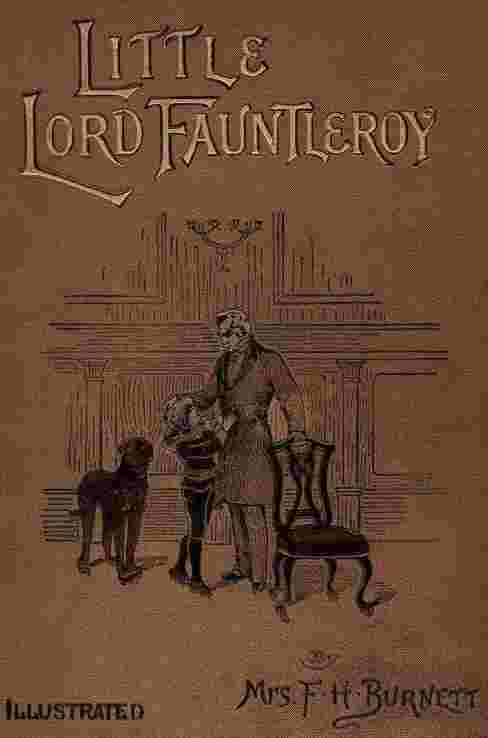

Figure 1.--Illustration from the first editions of "Little Lord Fauntleroy". These drawings had a major role in setting the popular fashion of fancy velvet suits for boys.

Figure 1.--Illustration from the first editions of "Little Lord Fauntleroy". These drawings had a major role in setting the popular fashion of fancy velvet suits for boys. |

Francis Hobson Burnett originally conceived of the Little Lord Fauntleroy story as a way of

entertaining her children. She published the book in 1886. She also published several other books,

the text and illustratins to which include interesting

discritions/illustrations of boys' clothes during the

late 19th Century and early 20th Century. She has two other very famous books. One was The Secret Garden, in which the rich boy, Colin, is often depicted in a Fauntleroy suit. It has also been

produced in film and TV productions as well as a Broadway musical. Another of her books was

The Little Princess, made into a notable 1930s movie staring Shirley Temple.

Mrs. Burnett's serialized story and the book were a huge success, eventually being translated into twelve

languages and selling over a million copies in English alone. By 1893, Little Lord Fauntleroy could be

found on the shelves of 72 percent of America's public libraries, second only to the Roman pot boiler Ben Hur. [Ann Thwaite, Waiting for the Party (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1974), pp. 94-95.] Contrary to its current reputatiion, Little Lord Fauntleroy was read and aclaimed by adults, including an American president and British prime minister.

After experiecing enormous success in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Little Lord Fauntleroy was little read. The Mary Pickford and Freddy

Barthomew movies stimulated some interest, but much less than the original book. While many children knew what a Fauntleroy suit was, they knew little about the

book itself.

Perhaps the most famous passage in Little Lord Fauntleroy is:

A few minutes later, the very tall footman in livery, who had escorted Cedric to the library door, opened it and announced:

"Lord Fauntleroy, my lord," in quite a majestic tone. If he was only a footman, he felt it was rather a grand occasion when the heir came home to his own land and possessions, and was ushered into the presence of the old Earl, whose place and title he was to take.

Cedric crossed the threshold into the room. It was a very large and splendid room, with massive carven furniture in it, and shelves upon shelves of books; the furniture was so dark, and the draperies so heavy, the diamond-paned windows were so deep, and it seemed such a distance from one end of it to the other, that, since the sun had gone down, the effect of it all was rather gloomy. For a moment Cedric thought there was nobody in the room, but soon he saw that by the fire burning on the wide hearth there was a large easy-chair and that in that chair some one was sitting--some one who did not at first turn to look at him.

But he had attracted attention in one quarter at least. On the floor, by the arm-chair, lay a dog, a huge tawny mastiff, with body and limbs almost as big as a lion's; and this great creature rose majestically and slowly, and marched toward the little fellow with a heavy step.

Then the person in the chair spoke. "Dougal," he called, "come back, sir."

But there was no more fear in little Lord Fauntleroy's heart than there was unkindness--he had been a brave little fellow all his life. He put his hand on the big dog's collar in the most natural way in the world, and they strayed forward together, Dougal sniffing as he went.

And then the Earl looked up. What Cedric saw was a large old man with shaggy white hair and eyebrows, and a nose like an eagle's beak between his deep, fierce eyes. What the Earl saw was a graceful, childish figure in a black velvet suit, with a lace collar, and with love-locks waving about the handsome, manly little face, whose eyes met his with a look of innocent good-fellowship. If the Castle was like the palace in a fairy story, it must be owned that little Lord Fauntleroy was himself rather like a small copy of the fairy prince, though he was not at all aware of the fact, and perhaps was rather a sturdy young model of a fairy. But there was a sudden glow of triumph and exultation in the fiery old Earl's heart as he saw what a strong, beautiful boy this grandson was, and how unhesitatingly he looked up as he stood with his hand on the big dog's neck. It pleased the grim old nobleman that the child should show no shyness or fear, either of the dog or of himself.

Cedric looked at him just as he had looked at the woman at the lodge and at the housekeeper, and came quite close to him.

"Are you the Earl?" he said. "I'm your grandson, you know, that Mr. Havisham brought. I'm Lord Fauntleroy."

He held out his hand because he thought it must be the polite and proper thing to do even with earls. "I hope you are very well," he continued, with the utmost friendliness. "I'm very glad to see you."

Litle Lord Fauntleroy was written by Frances Hodgson Burnett. She was born to a wealthy iron monger who lost his money and died when she was very young. Herbmother moved the family to America where they lived

in virtual poverty. Frances as a teenager began to submit stories and her earnings helped to sustain the family. Little Lord Fauntleroy was conceived in stories she used to tell her two boys. The Fauntleroy story itself reverses Mrs. Burnett's of from riches to rags, but the theme appears in other stories like The Secret Garden and The Little Princess.

Modern readers may find it difficult to appreciate the public aclaim with which Mrs. Burnett's book was greated. Both our cynical modern outlook and the modern

view of Little Lord Fauntleroy make it difficult to appreciate the reaction to the book when it first appeared. One literary critic writes, "It does not do to say merely that Little Lord Fauntleroy was a great sucess; it caused a great public delerium of joy."

The book had a double appeal to Americans. Many Americans readers were, and still are, very interested in European airistocracy. The book provided many

discribitions of the aristocratic lifestyle. Romantically inclimed American mothers were enchanted with the accounts of British airistocracy, not to mention the idealized Reginald Birch drawings of the young hero in his velvet suit. Even so, the story clearly hearled the superiority of the democratic American order as seen through the

inocent and pure hearted young American boy--Cedric Erol. To Cedric even after

becoming Little Lord Fauntleroy, his friends Mr. Hobbs (a grocer) and Dick (a shoe

shine boy) were just as important as his rich artistocratic as the Earl's

friends. Nothing could have been

more ingeniously designed to appeal to the American public.

Not fully understood today is the simple fact Little Lord Fauntleroy was

not written or published as a children's book. It was read by adults. Books

we would today describe as children's books were in the late 19th Century widely

read by adults. Many of the best sellers of the day were, in fact, books now

viewed as children's books. Examples include: Heidi (1884),

Treasure Island (1884), A Child's Garden of Verses (1885),

Huckleberry Finn (1885), King Solomon's Mines (1886). Only one

book broke the pattern in the mid-1880s, War and Peace which was also a

best seller in 1886.

Little Lord Fauntleroy was not just a popular suceess. It was also aclaimed by the literary

establishment. Reviewers such as Louisa M. Alcott (Little Women) raved about

the book.

Mrs. Burnett's book was even aclaimed by statesmen and political leaders.

Admirers included the U.S. Ambassador in England (James Russell Lowell) and the

British Prime Minister (William Gladstone). Gladstone actually stated that Little

Lord Fauntleroy would bring about "added good feeling" between America and England

and help them to understand each other. This was no unimportant matter in the

late 19th Century. It hould be remembered that the United States and England

fought a war in the 1810s. Another war could have ocuured in the 1840s over

the Oregon Territory. British policies

in Ireland during the 1840s resulted in a substantial number of new immigrants

with intensely anti-British sentiments.President Polk's campaign slogan was

"54-40 or Fight." The negative

sentiments toward the British expressed by Mr. Hobbs in Little Lord Fauntleroy

were widely held by many Americans. The

British for their part were sympathetic to the South during the Civil War

(1861-65) and an important element wanted to recognize the South. Interestingly,

it was Prince Albert, who also played an important role in the development

of modern boys' clothing styles, who argued persuavely against what would have been

disatrous for Britain--recognition of the South.

Little Lord Fauntleroy is Mrs. Burnett's best known book. The story was first published in serial form in the St. Nichols Magazine

during 1885. It was an immediate success. It was first published during 1886 in book form. An English edition soon followed. Publication of the book led to stage and after the turn of the century movie productions. The book has since been translated into many languages. Editions have continued to appear into our modern day.

Figure 2.--This is the cover of the first edition of Mrs. Burnett's "Little Lord Fauntleroy," the book that would influence boys' clothing and hair stles for a generation. |

Little Lord Fauntleroy has since 1886 been published in inumerable English as well as many foreign-language edditions. There is no difference in the English language text, except for some abridged

editions for younger children. The only important difference in the various editions are the illustrations.

Known editions of Little Lord Fauntleroy include:

Little Lord Fauntleroy: First edition, 1886 (Birch illustrations)

Der kleine Lord, Loewe, 1907. (Plonck illustrations)

Little Lord Fauntleroy Warne, 1925 (C.E. Brock illustrations)

Un Piccolo Lord, Florence, Salani, 1935. (Micheli illustrations)

Le Petit Lord Fountleroy, Nelson, 1938. (Bloch illustrations)

Il Piccolo Lord, Florence, Marzocco, 1940. (Fabbi illustrations)

Little Lord Fauntleroy, Glasgow, Collins-Lions, 1974. (No illustrations,

the editor complaining that the original Birch illustratiins were misleading.)

Mały lord Klasyka Dziecięca, 1998 (Pasierska illustratiions)

Il piccolo Lord, Turin, Utet, no publication date. (Terzi illustrations)

The first edition of Mrs. Burnett's book was illustrated by Reginald

Birch and it is his drawings that are most associated with the book. A

large number of illustrators from many different countries, however have

also illustrated the various editions. The book appears to have been especially popular in Italy. Art work for the many editions has been executed by noted illustrators from every major European country, including: Birch (American, 1886), Block (English, 1925), Bloch (French, 1938), Fabbi (Italian, 1940), Micheli (Italian, 1935), Pasierska (Polish, 1998),

Plonck (German, 1907), and Terzi (Italian, undated).

Navigate the Historic Boys' Clothing Web Site:

[Return to the Main Fautleroy page]

[Return to the Main literary page]

[Introduction]

[Chronologies]

[Style Index]

[Biographies]

[Bibliographies]

[Activities]

[Countries]

[Photography]

[Contributions]

[Frequently Asked Questions]

[Boys' Clothing Home]