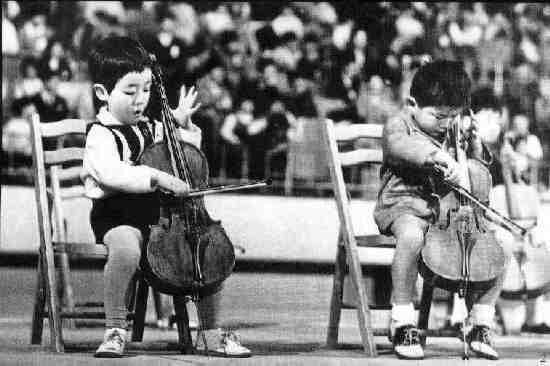

Figure 1.-These two little Japanese boys in 1970 at about age 3 are learing to play the violin. Both wears short pants, one with logt-colored tights.

Figure 1.-These two little Japanese boys in 1970 at about age 3 are learing to play the violin. Both wears short pants, one with logt-colored tights. |

A now famed Japnese music teacher, Shinichi Suzuki, reasoned that a child should be able to learn a musical instrument by four years of age or less. He noted how young children can easily master such complicated behaviors as the intricacies of speech or using chopsticks, Children can in fact learn these behaviors much more easily than adultsd. Suzuki concluded that children could also begin to learn musical instruments. The resulting Suzuki Method revolutionized the teaching of music in Japan, America, and other countries. It emphasizing the development of their listening skills at a very young age and teaching them to play entire works by ear before they learn to read music. His methods were inspired by his observation that children learn to speak their native language with great proficiency long before they learn to read. Philosophically, Suzuki saw music education as a

vehicle towards personal development and self-fulfillment. He encouraged his students to achieve their own happiness by

bringing joy to others through music.

Shinichi Suzuki was a violinist, educator, philosopher, and humanitarian. Over the past fifty years he had a profound influence on music education in his own country and throughout the world. Suzuki based his approach on the belief that, "Musical ability is not

an inborn talent but an ability which can be developed. Any child who is properly trained can develop musical ability, just as all

children develop the ability to speak their mother tongue. The potential of every child is unlimited." Suzuki's philosophy and the

method he developed have now reached thousands of teachers, children and families in many nations. When he died in January

1998, Dr. Shinichi Suzuki was mourned around the world. His belief in the marvelous capabilities of all human beings and the importance of nurturing these capabilities with love has left a lasting legacy.

Suzuki based his approach on the belief that, "Musical ability is not an inborn talent but an ability which can be developed. Any

child who is properly trained can develop musical ability, just as all children develop the ability to speak their mother tongue. The potential of every child is unlimited." Suzuki's beliefs and the method he developed have now reached thousands of teachers,

children and families in many nations.

Born in 1898, Shinichi Suzuki studied violin in Japan for some years before going to Germany in the 1920's. After further study there, he returned to Japan to play and teach. He taught university students, but became more and more interested in the education of young children. Suzuki realized the implications of the obvious fact that children of all nationalities easily learn their native language. He began to develop a method for teaching violin modeled after the way in which children learn language and called it the Mother-Tongue Approach or Talent Education.

Suzuki launched his pioneeting work after World War II. He was struck with how innocent children had to suffer because of the mistakes made by adults. He wrote, "These precious choldren had absolutely no part in the war and yet were the ones suffering most severely, not only in the lack of proper food, clothing and a home in which yo live , but more important, in their education."

Suzuki's work was interrupted by World War II, and after its end he was determined to bring the beauty of music to the bleak lives of his nation's children. He began teaching at a small school in Matsumoto, working to develop a sequential repertoire that would present musical and technical points in a logical manner. Within a few years Suzuki's students were amazing listeners with their abilities.

The Talent Education movement grew as other teachers studied with Suzuki and began to teach throughout Japan. The program expanded as teachers of different instruments became interested in Suzuki's approach, and materials were developed for cello, piano and flute. Over the years, thousands of Japanese children have received Suzuki training at the Talent Education Institute in Matsumoto or one of the branch schools in other cities.

In 1958 a Japanese student at Oberlin College brought a film of Suzuki's young students performing in a national concert. American string teachers became intrigued with the results of Suzuki's method and began to visit Japan to learn more about his work.

Interest intensified in 1964 when Suzuki brought a group of students to tour the U.S. and perform at a joint meeting of the American String Teachers Association and the Music Educators National Conference. The method began to flourish in the U.S. with visits of American teachers to Japan, performances of Japanese tour groups, and the growth of hundreds of Suzuki programs across the country.

Dr. Suzuki did not develop his method in order to produce professional musicians but to help children fulfill their capabilities as human beings. As he has said, "Teaching music is not my main purpose. I want to make good citizens, noble human beings. If a child hears fine music from the day of his birth, and learns to play it himself, he develops sensitivity, discipline and endurance. He gets a beautiful heart."

The Suzuki method is most associated with Japan where Dr. Suzuki lived and worked. The success of the method in Japan, however, has resulted in its adoption in many other countries. Through his life and work, Dr. Suzuki has inspired thousands of parents and teachers in more than 40 countries all over the world. Parents in Asia, Europe, Australia, Africa and the Americas have looked to the Suzuki method to help nurture loving human beings through the mother-tongue approach to music education. In the supportive environment fostered by the Suzuki method, children learn to enjoy music and develop confidence, self-esteem, self-discipline, concentration, and the determination to try difficult things-qualities that are sorely needed in our time. As Pablo Casals remarked through his tears after hearing Suzuki children play, "Perhaps it is music that will save the world."

More than 50 years ago, Suzuki realized the implications of the fact that children the world over learn to speak their native language with ease and began to apply the basic principles of language acquisition to the learning of music. The ideas of parent responsibility, loving encouragement, listening, constant repetition, etc., are some of the special features of the Suzuki method.

When a child learns to talk, parents function very effectively as teachers. Parents also have an important role as "home teachers" as a child learns an instrument. In the beginning, one parent often learns to play before the child, so that

s/he understands what the child is expected to do. The parent attends the child's lessons and the two practice daily at home.

The early years are crucial for developing mental processes and muscle coordination in the young child. Children's aural capacities are also at their peak during the years of language acquisition, and this is an excellent time to establish

musical sensitivity. Listening to music should begin at birth and formal training may begin at age three or four, though it is never too late to begin.

Children learn to speak in an environment filled with language. Parents can also make music part of the child's environment by attending concerts and playing recordings of the Suzuki repertoire and other music. This enables children to absorb the language of music just as they absorb the sounds of their mother tongue. With repeated listening to the pieces they will be learning, children become familiar with them and learn them easily.

When children have learned a word, they don't discard it but continue to use it while adding new words to their vocabulary. Similarly, Suzuki students repeat the pieces they learn, gradually using the skills they have gained in new and more

sophisticated ways as they add to their repertoire. The introduction of new technical skills and musical concepts in the context of familiar pieces makes their acquisition much easier.

As with language, the child's efforts to learn an instrument should be met with sincere praise and encouragement.

Each child learns at his/her own rate, building on small steps so that each one can be mastered. This creates an environment of

enjoyment for child, parent and teacher. A general atmosphere of generosity and cooperation is also established as children are encouraged to support the efforts of other students.

Learning music with other children promotes healthy social interaction, and children are highly motivated by participating in group lessons and performances in addition to their own individual lessons. They enjoy observing other children at all

levels-aspiring to the level of more advanced students, sharing challenges with their peers, and appreciating the efforts of those following in their footsteps.

Children do not practice exercises to learn to speak, but learn by using language for communication and self-expression. With the Suzuki method, students learn musical concepts and skills in the context of the music rather than through

dry technical exercises. The Suzuki repertoire for each instrument presents a careful sequence of building blocks for technical and musical development. This standard repertoire provides strong motivation, as younger students want to play music they hear older

students play.

Children are taught to read only after their ability to speak has been well established. In the same way, Suzuki students develop basic competence on their instruments before being taught to read music. This sequence of instruction enables

both teacher and student to focus on the development of good posture, beautiful tone, accurate intonation, and musical phrasing.

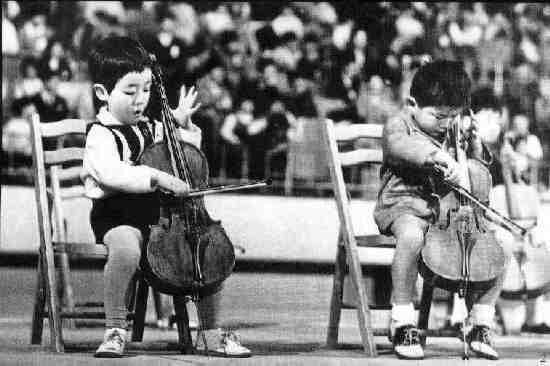

Figure 2.--These Suzuki trained children participated in a mass concert in Japan. Most of thev bous wore white shirts, ties, blue short pants, and white kneesocks. |

The children performing at a Suzuki recital in Japan usually wore white shirts, ties (sometimes bow ties), blue short pants, white kneesocks, and dark leather shoes. As the recitals are normally indoors they do not normally wear caps. The shorts are generally blue. The girls normally wear suspender skirts, but the boys do not wear suspender shorts. The most common socks were white kneesocks, but HBC has also noted tights, dark kneesocks and both white and sark short socks. Recital costumes in other countries were more varied, but in the 1970s they often copied the Japanese clothes.

Related Chronolgy Pages in the Boys' Historical Web Site

[Main Chronology Page]

[The 1880s]

[The 1930s]

[The 1940s]

[The 1950s]

[The 1960s]

[The 1970s]

[The 1980s]

Navigate the Historic Boys' Clothing Web style pages:

[Kilts]

[Caps]

[Sailor suits]

[Sailor hats]

[School uniform]

[Scout]