United States Boy Scout: Race

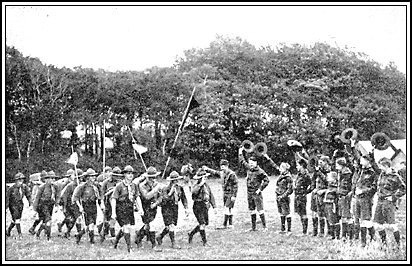

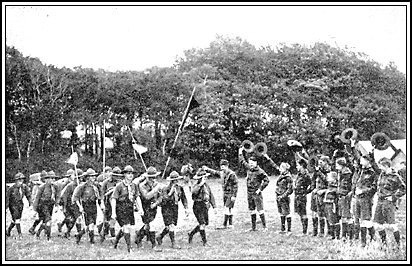

Figure 1.--American and German Scouts at the 1929 World Jamboree. A decade later these same boys would be locked in a titantic struggle for the vary future of the world--World War II. One of the fundamental issues at stake in the War was race--an issue that the BSA was just beginning to cinfront itself in the 1920s.

|

As in so much of American history, race has and continues to play an important role in Scouting. Race was as a factor in early American Scouting, especially in the South where early Scouters were determined to prevent black boys from entering the movement. The fact that the Baden Powell's Boys Scouts eventually decided upon an inclusive international approach to Scouting meant that to participate that an exclusive white program could not be mauntained, despite the attitudes of many in the movement. William D. Boyce who founded the Scouting movement in America was adament that it should be open to boys of all races and creeds--but his view was not shared by many. The BSA and YMCA alike were guided by adult volunteers who held socially progressive organizational goals. While their were some socially conservative elements interested in organizing a more overtly milataristic organization, the role the YMCA played in the early years of the BSA helped to imprint it with the YMCA stamp of social progressiveness. Enrollment patterns gave preference to middle-class boys in the early going. This was because these boys were the most interested and their parents could afford the program, all making organization easier. Later, both the BSA and YMCA reached out to lower-class youths, but with less favorable results. The leadership alternatingly displayed condescension and defeatism toward these poorer boys, and these youths often found the BSA and YMCA culturally alien. The BSA faced an even more difficult challenge when it came to black youthm especially in the South. Even in the north, Scouting in America from the beginning was a highly segregated activity. This is in part because many of the early sponsors were schools (many of which were segregated by law or demographic patterns) and churches (except for the Catlolics are among the most segregated institutions in America). Until the 1970s, fewer blacks than whites have particiapted in Scouting. A factor here is cost. We suspect that that there are other factors as well, some relating to why Scouting has had less appeal to the working-class in England. Many of the blacks that have participated have done so in largely black troops. This continues to be the case today. In fact Scouting is one of the most segregated youth activity in America. This is not because of BSA policy, but because of econonomic, cultural, and demographic trends in America.

Important decissions were made about Scouting in the 1910s which had a major impact on its character and success. There were many competing visions of the movement with varying influences including commercial, altruistic, patriotic, militaristic, social, religious, racial, and many others. In this regard the influence of the YMCA had a critical and lasting

impact on the direction of the BSA, especially the responsibility for community service. YMCA Executive Edgar M. Robinson played a major role in the early Scout movement. Surprisingly, his name is often not included on a list of American Scouting founders despite the key role that he played. Actually Boy Scouting in America began a makeshift

YMCA arrangement that had never been planned. Of course Edgar Robinson was a YMCA executive, but James West also was involved with the Y. Perhaps even more importantly many early troops were organized at YMCAs or by YMCA staff.

The Boy Scouts of America (BSA) was founded by William D. Bouce and several associates in 1910. Boyce was a businessman with an interest in youth work. His critical controbution to Scouting was to organize the BSA as a business. He incorporated the organization, choosing Washington, DC, rather than Chicago to emphasize its national character. He recruited key youth professionals, primarily from the YMCA, to design and operate the program, and he provided essential funding for the fledgling organization. Important decissions were made about Scouting in the 1910s which had a major impact on its character and success. There were many competing visions of the movement with varying influences including commercial, altruistic, patriotic, militaristic, social, religious, racial, and many others. The American Scout movement was relatively small in the 1910s before World War I (1914-18). The movement grew significantly beginning with the War when a patriotic fervor swept the country. The movement was to grow even more in the properous 1920s. Increasingly by the late 1910s it was becoming an excepted part of an American boyhood, at least in small towns and cities, to join the Boy Scouts. The organization became increasingly popular throughout the country and was supported by both schools and churches.

The character builders who so energentically approached the organization of white middle-class boys were not at all as interested in orgazing black boys. There were several reasons for this. Black boys were undeniable a much more difficult challenge. The black population was primarily located in the rural South and very poor. A variety of factors affected which children worked. The most significant was of course social class. Most of the children that worked were children from poor families that had to work. Their parents could not afford to send them to school and often needed their maeger earnings just to provide meer sustanance. There were, however, other factors such as demographics.

Rural children were needed to work on the farm. Urban children were more

likely to be sent to school. A major factor in the United States was race.

Note that in images of child labor during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, black children (especially the boys) are almost always

only seen as agricultural labor.

Racial Dilema

The povery and rural location posed major difficulties in themselves, but more was involved. The early 20th century character builders were white and even the most progressive of them were affected by a kind of "casual racism" that made it less urgent for them to focus on black youth. Many were unsure about organizing black youth in the north, organozing in the south was a virtual impossibility. The Southern white Jim Crow power-structure on whom the character builders needed to rely to orgnize white boys, was not just unconcerned about balcks, they were vehemently opposed to any effort at organizing them. To have challenged white leadership would have emperiled the organization of white boys in the South. Here it is easy to be critical. But would have it really been beneficial if the largely northern leadership of the BSA and YMCA had insisted on a more racially inclusive program? The result sure would have been that the BSA would have never received a Congressional charter and a probably a separate highly racist southern association would have been established which may well have appaeled to some northern whites. It may have also made it more difficult to eventually organize black BSA troops in the South. The various aternatives are difficult to assess, but in the final analysis BSA and YMCA leaders were simplly not that interested in black youth to jepoardize their national initaitives. America in the early 20th century was a rasist society and it can not be expected that the BSA, YMCA, and other youth groups would have somehow been unaffected by the prevailing racism.

Racism in British Scouting

Unlike America, few blacks lived in Britain in the 1900s when Baden Powell founded Scouting. Britain, however, governed a vast colonial empire populated by non-blacks. As a result of their position of power over these non-white populations, the uidea that whire Britons were superior people was a widely held opinion throughout Britain. Rudyard Kipling's poem, "The white man's burden," published in 1898, consisely summarized the attitude of the British people: "Take up the White Man's burden--Send forth the best ye breed--, Go, bind your sons to exile To serve your captives' need; To wait, in heavy harness, On fluttered folk and wild--, Your new-caught sullen peoples, Half devil and half child ...." [Kipling] Several authors have raised the issue of Baden Powell's racism. [Rosenthal, Character Factory] Given the iconic staturec of Baden Powell in Scoiting, many in the movement or influenced by the movement, object to any criticism of the legendary founder of Scouting. The objection is especailly vehement on the subject of racism and it is such a serious charge in the modern context. At the time of Scouting's founding, issue of race were generally regarded as of little consequence. There are many statements and writings by Baden Powell that are indeed blantanly racist and in the modern context, offensive. Even his serious defenders do not deny this. There are many examples. Baden-Powell's mnemonicdevice for 'N' in Morse code was a cartoon of 'Nimble Nig' (the dot) being chased by a crocodile (the dash). [Macleod, pp. 212-214] The general response to the charges of racism is that "B-P was no more racist than most Englishmen of his time, indeed in many ways less." [Buruma] Some authors do not accept this argument. One writes, "The issue, of course, is not whether Baden-Powell was more or less racist than anyone else, but whether his racist thinking tells us something important about the originator of a significant social movement whose professed ideals transcended race." [Rosenthal, letter]

Here we are not sure just how Baden Powell initiallu envisioned Scouting. The competition with the British Boy Scouts had a significant impact on Baden Powell and British Scouting, giving it a more international inclusive outlook. Indeed Baden Powell worked diligently to bring Scouting to non-white boys. He succeeded in India, but failed to gain Scouting for South African blacks. At the time British colonial officials opposed both steps. Baden Powell wrote in 1926, "The question stands with the politicians just where it did 20 years ago. They do not look forward to what is due to the native." [Buruma]

Racism in America

Racism was endemic in American society and culture in the early 20th century, from north to south. There were, however substantial regional differences.

The North

Blacks in the north for the most attended integrated schools and were able to vote. There were virulent race baters in the North as well as in the South. For the most part, however, race was not a major issue. Many northerns grew up with little or no contact with blacks. There little contact because few blacks lived in the North and those that did were heavily concentrated in specific areas of a few large cities. Not only was there little contact, but the black presence in America was largely edited out of the national consciouness. American children had no idea that black soldiers played an important role in the Civil War or that there were many black cowboys and unirs of black cavalry. News reporrs during the Spanish-American War downplayed the fact that black soldiers accompanied the Rough Riders on the charge up San Juan Hill. Even among Northern progressives there was what one historian calls a "casual racism" which was an accepted part of American and British culture. YMCA camp entertainment would include minsteral shows and other parodies of blacks. According to one historian, "YMCA men gave minstrel shows at camp and even parodied a 'colored' YMCA, laughing at the education committee's purported obsession with

chicken-raising." [Macleod, pp. 212-214] While these men would have been horrified at lynching or even denying black citizens the vote, few felt that balcks were the social equals of whites and this affected their outlook and influenced the policies adopted in the BSA, YMCA, and other organizations.

The South

There was nothing casual about the racism in the deep South governned by Jim Crow laws. Blacks were denied access to jobs, education, and basic government services. Laws separated the races at every social level. Separate meant inferior. Black schools were under funded and had poorly trained teachers. Text books were normally used ones retired by the white schools. School buildings were inadequate and poorly maintained. Blacks were denied the right to vote. Any one who challenged the system could face night riders and a lynching. The all-white law enforcement agencies not only did little to protect black citizens, but were often involved in the extra-legal terrorism. White racist state and local leaders saw education as a potential challenge to the system. Thus the idea of organizing black boys in what was at first seen by many as a para-military organization (early Scouts wore uniforms virtually identical to the U.S. Army) was dismissed out of hand.

The West

The West was more complex. As in the north, there were few blacks, but in some states there were localized populations if Indians, Chinese, and Japanese. More important was the substantial popuation of Hispanics (mostly Mexican Americans). There were some segreagated schools for these children. The complexity of the racial pattern, however made the dual system that was errected in the South, more difficult to fashion in the West, especially on a state-wide basis. A HBC reader reports that whay he remembers of school segregation in Texas (Texas is variously considered a Western and a Southern state) is that white and Hispanic children attended the same schools, and blacks were segregated. HBC does not know of any state that had a segregated Hispanic system, but we think they may have been some local school distruvts that had seperate Hispanic schools. This needed to be confirmed.

BSA Organization

There were substantial differences in the apparoch to black Scouting in the North and South. The BSA never at the national level rejected the principle of blacks joining mostly white troops or organizing black troops but they adopted policies that made it very difficult for black troops to be organized, especially in the South.

The South

The BSA decided ar an early point to require that all new troops be scantioned by the local councils. Thus blacks wanting to organize troops had to get the approval of all-white councils. Especially in the early years, Southern councils refused to approve any black troops. Alterntive approaches such as a request from a group of blacks to organize "Young American Patriots" was rejected by the BSA. One historian quotes Bolton Smith, a Memphis banker who was BSA board's expert on race relations, and answered a critic by saying, "as long as the grown people are willing to stand for the lynchings of colored people," it was futile to expect public support for black Boy Scouting. He insisted that to admit black boys "would lose us many white Scouts..." [Macleod, pp. 212-214.] YMCA executive E.M. Robinson played a key role in ealy Scouting.

He was disturbed that local councils were not approving black troops. The YMCA did have a program for black boys. George W. Moore was the Y's International Committee's secretary for

black boys. He designed an alternative to Boy Scouting that he called the Lincoln Guild. Robinson who was Scoutings first executive director during the critical ffirst year in 1910 did not implement the plan, insisting on centralized authority because, as he phrased it, "colored people are less responsible than white ..." [Macleod, pp. 212-214.] The use of the term "colored" and his interest in extending Scouting to blacks identifies Robinson as a progressive at the time on race issues. His comment shows that even progressive men at the time were influenced by what would now be seen as a deeply troubling racist outlook. Concerning the Lincoln Guild it may arguably have been for the best that the program was never implemented as although delayed, eventually black Scouting did develop. There were still areas of the country in the 1910s where local councils had not yet been organized. Here the BSA, following its policy of council approval, also refused to recognize black troops. BSA executive James West, who replaced Robinson as Scout excutive in 1911, saw "great mischief ... if we permit the organization of colored troops in some very small community, even with the consent of the superintendent of schools and other representative people. Suppose this small community eventually becomes part of a county council or district council--it would work havoc and be an unnecessary embarrassment to overcome." [Macleod, pp. 212-214.] Gradually as the puplic began to see Boy Scouts as a wholesome youth activity and not a threatening para-military group, opposition to black Scoting became less intense. The idea of black boys wearing what looked like a military uniform, still offended many. One report indicated, for example, that white Boy Scout officials in Richmond, Virginia, threatened that they would publically burn Scout uniforms if black boys were permitted to use them. [Macleod, p. 214.] The issue of the uniform is insightful and important. Althoughb not the case today, uniforms in the early 20th century were very popular with boys. In facr one of the reasons some boy were interested in Scouting was the uniform. We are not precisely sure why there was so much objection to black boys wearing the uniform. We suspect that the iniform being essentially the same as the U.S. Army uniform was viewed in patriotic terms. And many whites at the time did not see blacks as true or real Americans. Also there is an element of authority associated with any uniform, especually the U.S. Army uniform which unerved many whites.

The North

Northern attitudes toward black Scouting were more complex and varried. Boys' clubs like the YMCA predated Scouting. The clubs were organized in mostly large northern cities and often were designed for immigrant and working-class boys. While the pattern varied, many accepted black boys and had integrated programs as early as the 1880s. Some early big city Scout troops (Buffalo and Philadelphia) alsi had integrated programs, usually mixing immigrant whites and blacks. This was, however, not the general pattern. Scouting tended to be more middle class than the Boys' club program. Early troops tended to be small and formed from boys of similar backgrounds. As a result, most black boys joining the Boy Scouts primarily joined black troops with black Scoutmasters. This was not a deliberate policy of the BSA, in some cases local councils did promote segregation. As one historian reports, "Although much segregation within the Boy Scout movement followed more or less automatically from the prior segregation of the institutions which sponsored troops, some was deliberately imposed in addition." [Macleod, pp. 212-214.] BSA officials in Camden, New Jersey, for example, took action with a black minister successfully recruited large numbers of black Scouts. This was not the general pattern. One study shows that in the 108 active councils in 1926 there were only 4,923 Boy Scouts under black leadership in 108 councils. Blacks were claerly under represented even in northern states. One survey in the late 1920s reported that in 10 northern communities 5.7 percent of the boys were black but that only 1.9 percent of the Boy Scouts wwere black. A historian concludes, "This poor representation possibly owed as much to poverty, however, as to direct racial exclusion. [Macleod, pp. 212-214.]

The West

We do not at this time have information on what transpired in Western states and the participation of Hispanic, Indian, Chinese, and Japanese boys in Scouting or the organization of troops in their communities. We think that given the groups sponsoring troops, especially churches, that many Hispanic, Chinese, and Japanese boys did participate in Scoting in largely distinct troops. There were for example ethnic Japanese Scout troops in each of the major internment camps during World War II (1942-45). One report describes how the Scouts at one of these camps defended a flag pole from adults alientated by their internment.

Gradual Acceptance

There was no black Scouting in the South throughout the 1910s and early 20s. There were a handfull of black Scouts in border states. There were reporredly 500 black Scours in Louisville Kentucky in 1924. An "advisory council" of prominent blacks acted under the supervision of the white counciol. This lack of black Scouting dod not begin the change until 1926. At that time the BSA convinced the Laura Spellman Rockefeller Foundation to provide the funds for a promotional campaign. I do not know the details pf the campaign, it may have been aimed more at the white councils than actual black youngsters. Gradually the white southern councils were persuaded to approve applications from black troops. Again we have few details, but do not belive that the white councils took any iniative to recruit black Scouts, but they did begin to accept segregated black troops. Some adult southern SDcouters still balked at the idea that black Scouts would wear the uniform. On the other hand there were frirndships on the personal level betwen black and white boys. [HBC note: Especially in rural areas where white boys may not have had many white playmates, often close friendships formed between white and black boys. White parents generally tolerated this when the boys were young, but began to discourage it once the boys became teenagers.] There are reports of white boys coaching black youngsters on Scouting and passing on used uniforms once the local councils began accepting black troops. [Macleod, p. 217.] All this sounds condescending today, at the time many black youngsters in the South could not have afforded to buy their own uniform. While the local councils began to approve blacl troops, we are not sure that they fully involved black Scours in activities planned by the council. In fact we think this is unlukely, but have few details. The development of black Scouting was painfully slow. The BSA Soouther field execitive, Stanley Harris, field executive for the South, reported that in 1939 pnly an estimated 50,000 of the America's nearly 1.44 million Scouts were black. [Macleod, pp. 212-214.]

The Civil Rights Movement

After the Supreme Court struck down segregated education in 1954 with the land-mark Brown vs. Topeka ruling, Americam began addressing issues of race in earest. The Civil Rights movement was resisted with violence and terror in many Southern states. Gradually the Federal Government managed to succeed in gaining basic cicil rights for black citizens in the South through the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Court ordered integration was underway by the 1970s. The BSA in the 1960s began to aggressively recruit black Scouts. One historian reports that by the late 1960s that blacks participated in Scouting in about the same proprtion as whites. [Macleod, p. 301.]

The BSA Today

Racism and issues of cultutal diversity continue to affect the BSA even today, although the issue most discussed today is sexual orirntation more than racism. A group called "Scouting for All" suggested to the BSA that they, "should create a new cultural diversity merit badge for youth in scouting. This merit badge would include requirements that would teach youth about cultural diversity, conflict resolution, and how we can help end sexism, homophobia, racism and discrimination among their peers." [Cozza]

Sources

Buruma, Ian. Review of Tim Jeal's biography of Baden-Powell, New York Review of Books, March 15, 1990.

Cozza, Scott. President Scouting for All, letter to Roy L. Williams, Chief Scout Executive National Headquarters, Boy Scouts of America, August 20, 2001.

Jeal, Tim. Boys Will Be Boys, a biography of Baden-Powell

Kipling, Rudyard. "The White Man's Burden," McClure's Magazine February 12, 1899.

Macleod, David I. Building Character in the American Boy: The Boy

Scouts, YMCA, and Their Forerunners, 1870-1920 (The University of Wisconsin Press,

1983), 315p.

Rosenthal, Michael. The Character Factory

Rosenthal, Michael. Letter, The Mew York Review of Books, June 28, 1990.

Christopher Wagner

Navigate the Historic Boys' Uniform Chronology Pages:

[Return to the Main chronologies page]

[The 1900s]

[The 1910s]

[The 1920s]

[The 1930s]

[The 1940s]

[The 1950s]

[The 1960s]

[The 1970s]

[The 1980s]

[The 1990s]

[The 2000s]

Navigate the Historic Boys' Uniform Web Site:

[Return to the Main U.S. Scout page]

[Return to the Main U.S. country page]

[Activities]

[Biographies]

[Chronologies]

[Countries]

[Essays]

[Garments]

[Organizations]

[Religion]

[Other]

[Introduction]

[Bibliographies]

[Contributions]

[FAQs]

[Questions]

[Unknown images]

[Boys' Uniform Home]

Navigate the Historic Boys' Uniform Web organization pages:

[Return to the National Scout page]

[Boys' ClubsYMCA]

[Boys' Brigade]

[Camp Fire]

[Hitler Youth]

[National]

[Pioneers]

[Royal Rangers]

[Scout]

[YMCA]

Created: August 3, 2002

Last updated: August 3, 2002