Individual World War II Accounts: Fujioka Keisuke

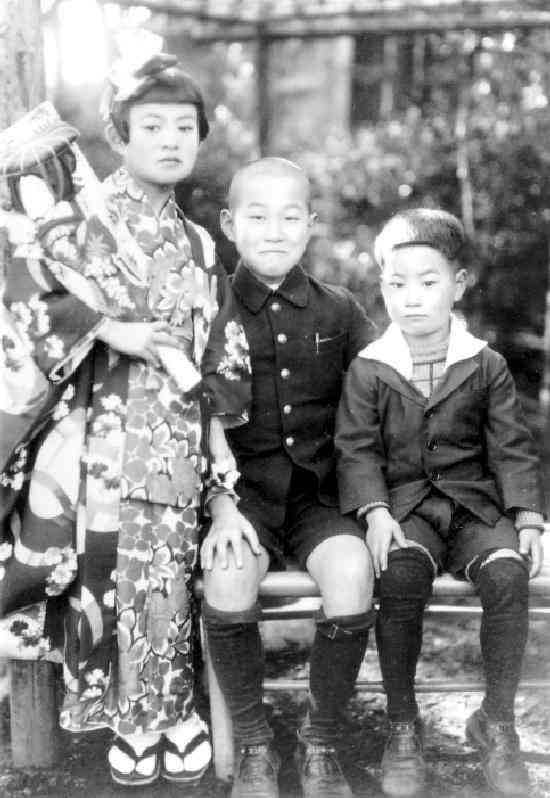

Figure 1.--Here is my family on New Years Day 1940. It was a family tradition to take a New Years portrait. My sister and I are wearing our best clothes. I had not yet begun school. My brother was in the last year of primary school and wears his school uniform. Note how we boys wear Wrstern clothes while our sister wears traditional Japanese clothes.

|

I am very pleased to hear that you are preparing a section on the post World War II

American occupation of Japan. I was born in 1934 in Tokyo. I and my family were in Tokyo during the American bombing. The terror and destruction were overwealming, just like Dresden. Our house was destroyed by incendiaries and we went to live in a rural village. I think most Japanese were surprised with American occupation policy. I was second son of a publisher. My father was a socialist in pre-World War II Japan but there were strict Government controls. After Japan surrendered and the American occupation began, father enjoyed freedom to publish Marx, Engels, and Lenin under Macarthur's regulations. My memories are somewhat limited because I was only a young child, but you may find them of interest. I will tell you what I remember, both about life in Japan during and after the War.

Family

I was born in 1934 in Tokyo. I was second son of a publisher. My family ( 5 persons of my parents, elder brother, sister, and I ) were living in the district NAKANO, which is 30km west from the center of Tokyo. Because of my father's publishing, we were very prosperous.

Socialism

My father was a socialist in pre-World War II Japan but there were strict Government controls. My father published articles, but not on socialism. His work was on ethnology

and history. As a result of his work, during the war, my mother was the richest in the neighbourhood. I remember during the War that a policeman ( or a military police ) came periodically to our house very calmly and politely. It was to observe our family. In the front room, there was a bookcase full of the socialist books which my father had published before the war. The book case had a glass front covered by a white curtain. The policeman usually sat against the bookcase. He made no effort to see what was in the book case. He seemed to me very happy as he could have a time with the richest woman in his district. I was still quite young. In this room, my father told me and my sister that Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were the greatest people in world history. And he prefered Lenin to Stalin.

Boy Scouts

During the War, there was no Boy Scouts in its true meaning. Boy Scouts was introduced to Japan in 1920. During the war, the purpose was cahnged along with the name to be a patriotic organization. It was run by one of the govenmental branches as part of the enthusiatic Anti-American movement. After the war, in 1948, Boy Scouts has returned to the original activities. I have little information on this as I was not involved with the Scouts.

New Years 1940 Portrait

Taking a photograph on New Years was a family tradition. This photograph was taken on New Years January 1, 1940 (figure 1). This was the most important and happiest day of the year. Every family celebrates New Year, and take pictures at home, or at the nearby shrine. I am Kei-suke on the right, the second son, 6 years old. I had not yet begun primary school, but my sistervhad and my broither was in his lastyear of elementary school. I wear my best cloths and shoes. Jun-suke in the middle, the first son, 11 years old, and next April, at 13 years old, he will enter a junior high school (public). His cloths will be a standard and formal one for older boys who go to school. He has a fountain pen in his breast pocket. He had his hair close-cropped, as usual for older boys. Ei-ko, the daughter, 8 years old. she wear FURISODE (a kind of Japanese costumes ) , TABI (white socks) and POKKURI (wooden shoes, GETA). This FURISODE is the special one for special events. She has a Japanese battledore in her arms. This battledore was not for play, but only for formal occassions. It has a big decoration of a doll on the front. There were less expensive battledore that children did play with. We children liked playing battledore and shuttlecock on the street.

National Boy

"national boy" ―― yes, it certainly sounds strange. During World War II, we boys and girls were called "Shoo Kokumin", literally, "Shoo" means " a little ", and "Kokumin" means "people". And in this context, it means " a little boy who are going to fight in the battlefield in near future against "Onichikushoo " (ogre and brute incarnate) American and English. We changed the meaning of the primary school in April of 1941 from the ordinary primary school to "Kokumin-primary school". Really, we use this "Kokumin" in the meaning of the people who have the Emperor, the God who prevail over the world. From the day August 15, 1945, everybody stops calling us "Shoo Kokumin". And we forget the words, "Shoo Kokumin"

forever.

School

Our school year begins in April and ends in March. I was a First class boy in the primary school. I had already been " a national boy " .

I learned about the the declaration of war in school on December 8, 1941. I hurried home to tell mother about the war and remember being disappointed to learn she and father already knew about it.

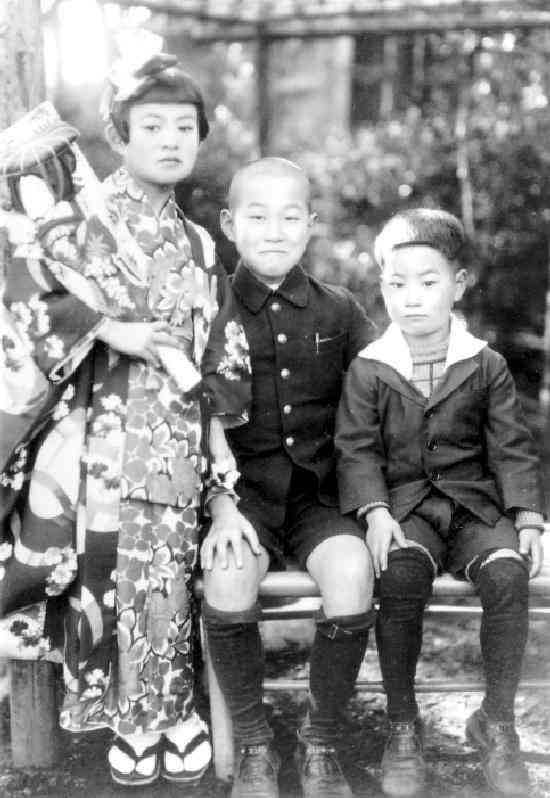

Figure 2.--This is the family portrait taken on New Years 1942 right after World War II with the United States began. I am dressed up for the portrait. This is what I wore to go to school. I was in the first grade. My older brother wears proudly wears the uniform of his Junior High School. My sister went to the same primary school as me, but was in the third grade.

|

New Years 1942 Portrait

This photograph was taken of my family during World War II on January 1, 1942, on our ENGAWA ( a narrow board-floor space, a kind of veranda.) I will list my family members from the right (figure 2). My brother Jun-suke began his first year in junior high school in April 1941. He wears a standard uniform of the school. In these

days, all of the boys could not advance to the junior high school even in the city. Some of them instead had to begin working. High school boys were proud of being able to continue his studies. They usually carried a cloth shoulder bag on their shoulders with textbooks notebooks, English-Japanese dictionary, and writing materials (pencils, eraser, triangles, compasses, and French curves.) Younger boys looked up to them. Next is

Jun-kichi, our father and of the family, 40 years old, a publisher. There there is me,

Kei-suke. I had begun my first class of public primary school in April 1941. The public school changes names from the number to the name which has some meaning when we broke into World War II on December 8, 1941. My school's name is KEI-MEI, which means enlightenment. I have a white name card on my chest. Usually, I do not wear these clothes, but must have the tag even at the new year party. Then there is Asa, our mother, 42 years old. She wear KIMONO, and KIMONO is usual clothes for adults woman. She taught me reading and writing, and multiplication tables before going to school. My sister Ei-ko, is in the third class of the same public school as I. The left two are my brothers-in-low, both over 20 years old. They were drafted soon after this photograph was taken.

American Bombing

During 1944 and 45 I actually observed with my eyes a Japanese fighter ram into a Boeing B-29 voluntarily and crashed out of the sky. Sometimes an engine fell to the ground with a big noise, and sometime a pilot jumped with a parachute. I am not sure he was a Japanese or not. We children were just scared and adults were afraid of asking about the facts.

Civil Defense

At night, civilians were prohibited from brightly lighting rooms. Every house covered room lamps with a piece of cloth when B-29 raids began on Tokyo. If one forgot it, air raid wardens (always men) who were responsible for checking on the blackout knocked windows or doors and cried loudly. With the low light levels it was impossible to read. We were not even allowed to listen to music. The wardens said that the American would have a chance

to look down and listen to our living.

Tokyo

I and my family were in Tokyo during the American bombing. Evry house had a shelter in Tokyo, but very small ones. Our house had a broad garden, and we could have a big

concrete shelter in the garden, about 10 m x 10 m. Bombing was not direct to our house at the first stage, and my brother climbed up onto the roof to observe the situation. The terror and destruction were overwealming, just like Dresden. The Americans in 1945 conducted to large B-29 bombing raids on Tokyo during March and May. (Japan received the Potsdam Proclamation August 15.) Our house was completely burnt in the May bombing raid. My brother ( he was 17 years old ) when the B-29 incendiary raid began climbed up the roof of the house and brushed sparks with a wet rag and a broom in vain. Our house has disappeared after 2 hours When our house was burned, my father and brother, and some of neighbers came to the shelter as usual with food. Most of the children in Tokyo was forced to evacuate in a group, or in a few instances with their family.

Nogisawa Village

I was taken to a small village, Nogisawa, in Fukushima Prefecture with my mother and sister, while my father and brother stayed in Tokyo. My brother eventually came to Nogisawa village to join us. My father stayed in Tokyo at his friend's house which was unburned. In Nogisawa village I saw an American fighter who was machine-gunning. It was a summer day. I was swimming in the river Abukuma. Suddenly, a fighter came to the village, and began to machine-gun the railway-station. I can remember vividly the head of the pilot in a white scarf, and I cried "Go to hell, this American !!" , laying in a narrow footpath between rice paddies. Despite that encounter and our evacuation from Tokyo, I was a happy boy, I think. I enjoyed every change around me. I loved the country life, and went to school with the country boys cheerfully. After school and during the summer holidays, I spent much time in the river side and the mining field. Sometime I worked in the rice-field and in the barn making straw sandals with an old man and his children.

School

In Tokyo, my elementary school (six grades, each grade had 5 to 6 classes) had a thousand boys and girls. In Nogisawa village, the school had only a hundred children. But the textbook was the same one. All of the textbook was compiled by the Ministry of

Education. There was no choice. As a matter of course, there was a large gap in schooling. But, I remember only the class of music in this village school. I could sing a song loudly without any fear to disturb the harmony with classmates. they were not so well in

singing a song. School lessons did not continue normally after the War began. In second grade, we had morning and afternoon two shifts. I don't know the reason why we had the shift. It would be because of school management of the wartime. Perhaps fewer teachers were available. We never had drills practising attacks on the Americans and never made bamboo spears. In our junior and senior high school, and college and university, there was

instructor ( teacher ) who conduct military exercise. He was an ex-serviceman. My brother had experienced physical education under the strict control of this veteran. My brother still now has no good impression. Most of the teachers (military exercise) were ex-servicemen of low ranks, and they had no education in junior high

school, only from primary schools. They were generally suffering from an inferiority complex to high school students. Very arrogant and barbarous. To my happiness, I have not experienced their exercise in my school days, but after the War, in our junior high school, there was a graduate of the Naval Academy. He was a teacher of physical lesson, and he liked to slap boys in the face over trifles. He was also the coach of the baseball club of the school. I disliked him, and did not joined his club.

School Uniform

There were two kind of schools; public ( municipal ) school and private school. Private school had their own school uniforms. Rich family sent their children to private school located far from their residence, and children generally went school by train or private car. My school was a public one, and I am not sure whether there was a uniform or not. There would be some consensus of children's costume. At elementary school there was a school cap. Every boy wore these caps with the school badge. This was the fixed rule. Girls did not have these caps. I didn't like them. In hot summer days, the brim of the cap soon broken by my heavy sweat, because it was made of some paper materials. In summer, we covered

the caps with a white cloth. There was no rule about the jacket, but we all wore short trousers. There was no rule about shoes, but we all wore canvas shoes. For shopping and special loccassions with the family in the town, we wore leather shoes.

Clothes

Obtaining clothes was very difficult, especially in the last years of the War. We wore what ever clothes that we could find. Most of our clothes were hand-me-downs. I usually got my older brother's clothes. My mother also bought some clothes on the black market.

Hair Styles

Both boys and girls had their hair cut in bangs. Boys had the hair at the back of their head cut short. Girls wore theirs cut long to shoulders). And at grade 4 or 5 they had their hair cropped closely. In 1942 every boy had his cut closely, amost shaved heads, to show our mind was with the soldiers at the front. I didn't like having my hair cropped.

Other City Children

While I stayed with my family when we left Tokyo, this was actually very rare. Most children were sent to the country side in school groups. They were parted from their parents, and placed under the care of their school teachers. I have a friend who was one of those children. He will provide an account of the housing, food, and schooling.

Expected Invasion

Everone expected that there would be an American invasion. We were told to resist the Americans when the invasion came. We had no real weapons, but at school we children were told to use bamboo spears. All very fantastic!! Nogisawa village is 100km far from Tokyo, and our teachers had no knowledge of how to meet the enemy.

Food

I will tell you in the next mail how our people had to go our looking for food to buy. There was a word "bamboo-shoot life". That meant to live by sellig things we had, like exchanging clothes for rice with the farmers in the country.

The Atomic Bomb

The atomic bomb is a sad memory for us here in Japan. Our people had no enough information on Hiroshima and Nagasaki disaster at the time of bombing. In 1950, we had a semi-documentary movie "The Bell of Nagasaki", by which our people knew the never-forgotten disasters done by the American barbarism for the fist time.

I can tell you that sooner or later, Japan would have surrendered to the Allied Powers without any major American invasion. We were too busy just trying to survive.

End of the War

My mother and our teachers did not tell us how the war going. We all listened to the radio on August 15, 1945, to hear the Emperor. It was the first time he ever made a radio address and people heard his voice. I am not sure who informed us that it was important to listen to the radio at noon. His voice was very hoarse, and everybody could not understand well what he actually said. No body cried. In a week, I was told by my mother we could back to Tokyo soon. My mother was a very sensitive woman. She had dream about the eldest son of the family with whom our family rented a room in the house. She knew the son by the photograph, but had nevermet him. In her dream, the son came back very heartily and he talked much things about the Chinese battlefield where he had fought the Red Army. The next day, the family received a letter which informed them of his death in battle. She cried, and the family cried much.

The Emperor

We call the Emperor "TEN-NOU-HEIKA" . This sounded very serious to us children. In our schools, there was some special shrines dedicated photographs of "TEN-NOU-HEIKA and KOU-GOU-HEIKA" . We had never seen the inside of the shrine, but we took off our cap every morning in front of the shrine. Teachers and newspapers sometimes called them "ARAHITO-GAMI". ARAHITO-GAMI means God who appeared in this real world in the figure of human being. I remember in 1947 or 49, talking to a friend about the facts of life as small boys often do. After I explained what little I knew, he asked me if KOUGOU-HEIKA (the Emperor) did the same as our common people.

American Occupation

After Japan surrendered we returned to Tokyo in November 1945. We could not live in one house in Tokyo, but my father found a house in the Nakano District, the same area we lived before. I do not recall seeing either GI or a jeep. When the American occupation began, father enjoyed freedom to publish Marx, Engels, and Lenin under Macarthur's regulations. He was not surprised though, he always conceived this day coming. Despite all the War-time propaganda, I beleive there was no fear of the American soldiers. MacAther was introduced us as a hero in the movie, and he was one of the greatest generals in the world, he graduated from Westpoint at the top. Our people were completely concerned with getting food, jobs and

housing. There was gradually a realization that the Americans actually liberated us. Generally speaking, American soldiers were very honest, kind and simple young men--not unlike the way they are portrayed in Hollywood post-war movies.

As a Socialist you might think that my father would have objected to the Americans. Actually my father was very busy criticising the war criminals and creating a new publishing system in post-War Japan. Sometimes, he said he had good impression for GHQ in their democratic policy and manners. About democracy. Some believe it was imposed by the Americans. I think that our people did not think democracy was imposed by American. That was a hearty call of our people. They had been terribly oppressed for a long time by the Emperor system and militarism.

Rationing

As I was a child, by recollections of rationing are limited. I remember we had some notebooks and tickets for food, clothes, salt and sugar. The most important one was the notebook for food (rice ?? we call it Beikoku-Tsuuchou). This notebook was used not only for food, but also for the identification card and license in the life of the post-war people. ( Now, the driver's license has the same usage as the food notebook. in our living in selling books, and buying some medicines. etc.) Children did not have their own ration book. There was one notebook for each family. Tickets, I don’t know. I don't know what allocations of food and clothes, but I can tell you, we could buy nothing by these notebook. Even if a rice shop had had some stocks behind his counter and we had had the due remainder for allocation in the note, he would say he have no rice to sell. Clothes was the same situation as food. Our people had had to buy some second hand clothes for their children , or in barter.

The Black Market

In Tokyo, there was special areas ( Ueno, Shinbashi, and Shinjyuku) to sell illegal goods. Open market, it would be. There, we could buy gloves, belts, knives, jackets of leather, clothes, materials for dresses, cigarettes (Camel, Lucky Strike, I remember clearly), chocolates cookies, canned foods?? Most of them were goods stolen or sold by illegal channels from Japanese army or after the occupations items that came through a variety of illegal means from American sources. I was a boy, and have no chance to buy these illegal goods for my own use, but several times I had been in Ueno with my mother or brother to buy some necessities of daily life. There was many little stalls which serve hot noodle and soap. And in the residential area, also we could by food and clothes in a familiar shops by black prices, and by peddlers.

Post-war Fashions

I do not have a lot of informtion about post-war boy's fashion. I think there was no American-styled clothing for children. I do know that our young girls earnestly wanted to get some fashion magazines (American magazines) to make their dress and hair style, I can tell you. American boy's clothes were not imported at the time of the post-war. In our modern history, we look at Europe (especially, England in the fashion of gentleman) as our good example. After the war, all of our life style has changed. Fashion, food, music, people's manner was heavily influenced by American movies. American democracy, you would say it. Blue jeans?? I am not sure when our people began weaing American blue jeans. Our people think cotton one-piece wear for women is very casual one, and not allowable to have in the outside to meet with people. Our culture based on silk. We think jeans (overalls) are for carpenters. Sunday carpenter, painter, etc. are new words. Generally to say, our life style completely changed in the 1960s.

Reader Comments

A Japanese reader comments, "I found this account of a "National Boy" very interesting. I hve heard of this term before and it was not mentioned so far in school. I am glad that you have created such an important page for us Japanese."

New Book

Keisuke Fujioka San informs us that he has translated the Charles Dickens book Sketches by Boz into Japanese. ( Boz was a pseudoname for Dickens early in his career. ) Keisuke San tells us, "One or two sketches from "Sketches by BOZ" was translated into Japanese in the 170 years since it was published in England. It did not prove very popularis 100 years, but was not popular among our people. I have attempted to translate Dickens ina more complete way. Our people, especially young people, think Dickens is old

fashion, difficult to read, and not interesting, but I think most of their complaints about Dickens come from the problems of translation. Iwanami Shoten will publish the part of "TALES" in two volumes in their Iwanami library during October 2003.

Keisuke Fujioka

HBC

Navigate the Boys' Historical Clothing Web Site:

[Return to Main World War II Pacific air campaign page]

[Return to Main World War II aftermath page]

[Return to Main Japanese page]

[Introduction]

[Activities]

[Biographies]

[Chronology]

[Clothing styles]

[Countries]

[Bibliographies]

[Contributions]

[FAQs]

[Glossaries]

[Satellite sites]

[Tools]

[Boys' Clothing Home]

Created: February 15, 2003

Last updated: August 25, 2003