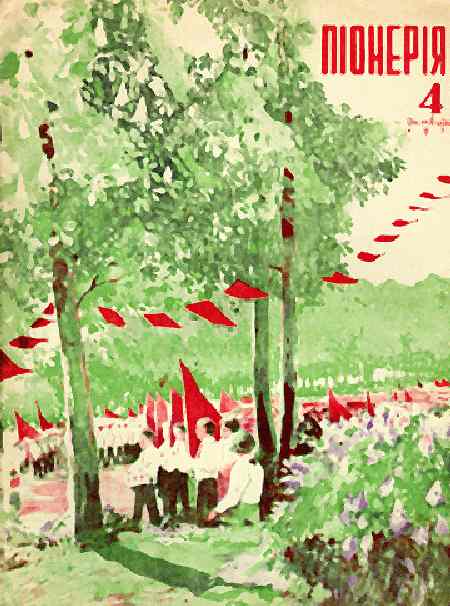

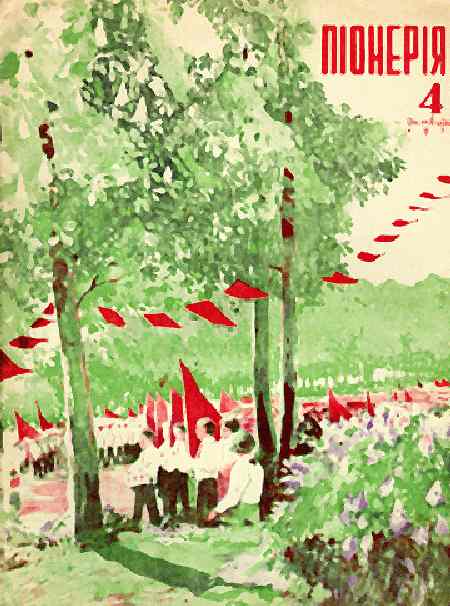

Figure 1.--This April 1935 edition of Pioneriia was one of the first issues of the magazine. It was a magazine for Young Pioneers and school children with stories, poems, drawings, and articles dealing with social and political issues.

Figure 1.--This April 1935 edition of Pioneriia was one of the first issues of the magazine. It was a magazine for Young Pioneers and school children with stories, poems, drawings, and articles dealing with social and political issues. |

Soviet children's literature was also strongly affected by the varying economic and political policies adopted by the country over time. Of course all literature is affected by chronological trends. There were heated debates in Russia over children's literature. In this regard, the trends in Soviet literature as for most of Soviet history, publication was controlled by the Communist Party reflected the official policies rather than the wider range of social though prevalent in Western literature. One literary historian, Ben Hellman, divides Soviet childrens literature into six periods--strongly associated one way or the other with the life and legacy of Soviet dictator Josef Stalin. We have slightly altered this to seven periods, believing that the World War II and post-War eras had quite destinct characteristics. Despite the trumoil, from the very beginning the Bolsheviks believed that children's books, as others forms of literature, should promote Communist ideology and authors that were not approved by Party officials should not be allowed to publish. The opening permitted by the New Economic Policies (NEP) introduced in the 1920s resulted by what has been called the Golden Age of Soviet children's literature. There are some creative Soviet books, but by the 1930s Stalinist orthadoxy had taken hold. Authors fully aware of the horros of the Gulag could hardly be expected to pen creative works. Even after Stalin's death in 1953, there were very real limitations placed on Soviet authors. As is often the case in totalitarian socities, core Soviet values are often represented in children's literature. The Soviet Union in August 1939 signed a Non-aggression Pact with NAZI Germany, becoming a NAZI ally in all but name. This sharp swing in Soviet policy was not, however, reflected in children's literature during August 1939-June 1941 by any effort to paint the NAZIs in a more favorable light.

The October 1917 October Revolution brought the Bolsheviks to power in Russia. Peace was negoiated with the Germans at Breast Litosk (1918) allowing the Soviets to pull out of World War I, but at a great loss of territory. Several years of Civil War followed between the Red Army and White forces, the Poles, and intervening foreign countries. Despite the trumoil, from the very beginning the Bolsheviks believed that children's books, as others forms of literature, should promote Communist ideology and authors that were not approved by Party officials should not be allowed to publish. he Bolsheviks needed new publishers to take the place of the Tsarist publishers. They also needed a new generation of writers to follow the Party guidelines.

Maksim Gorky played a major role in the initial phase of Soviet children literature. The Bolsheviks rulthlessly crushed all opposition, but deteriorating economic difficulties forced Lennin to reconsider early economic initiatives. introduce the New Economic Policies (NEP) in 1921. As part of the NEP program, writers were given more freedom and the impact on literature, including children's literature, was pronounced. Raduga (The Rainbow) began publishing in 1923. Literary historian Ben Hellman sees it as the beginning of the Golden Age of Soviet Russian children's literature. An especially creative group of young writers and illustrators worked for Raduga. The Communist Party founded Soviet youth organizations (the October Children movement, the Pioneer movement and Komsomol) during the 1920s to exert control over children and youth culture--a key step in any totalitarian society. Thus organizing the children into Young Pioneers was an important activity, conducted primarily at school. School text books, other books, periodicals hekped support the new Pioneer movement and defined the role of a good Young Pioneer in the new Soviet state. Stories often desctibed the very difficult life of Russian children before the Revolution--especially experiences of serfs and worker's children. The role of children in the Civil War was another common topic. Admist this outflowing of creativity, Stalin had by the late was emerging as predominat Soviet leader following Lenin death in 1924, a development which would have a profound impact on Soviet society and literature.

Stalin during the early 1930s consolidated his hold over the Communist Pary and Soviet state. He launched an ideological crusade which covered his true intent to eliminate any actual or potential opposition to his laedership. Soviet children's literature as other cultural elements was assessed as to its ideological issues. One of the major issues was the suitability of fairy tales or fantasy literature generally in a socialist society. Gorky returned to the Soviet Union in 1928 to grat acclaim. He played an importtanr role is Soviet kiterature until he was caught up up in the Stalinist Terror. He was probably killed by Stalin in 1936, but because of his reputation was not attacked opoenly.

The Union of Soviet Writers was formed in 1932. A special section was set up for children's writers. The professional journal Detskaya literatura (Children's Literature) was also founded in 1932 by a publishing house with the same name. Marshak spke about children's literature at the First Congress of the Union of Soviet Writers. He made it clear that socialist realism obligatory for all children's authors. Wriyers who did not comply woukd not only not be published, but risked disappearing into the Gulag. The Party could force writers to comply with the ideolgical requirements, but it could not ensure the output of the smar quality of literature that had been crearted during the Golden Age. In fact the Party's requirements virtually guarnteed the production of stilted, hackeyned stories of minimal literary quality. Witers were well awate that if Gorky could be killed, none of them wre safe. The Stalinist purges of the 1930s eliminated many creative authors and terrorized authors from any kind of creative work. Some of the most important themes were industrialization and the collectivization of farming--hardly a topic that could excite many children. Other important themes were solidarity with the communist movement in other countries and military readiness. There was also biographies about the Revolution, especoally Vladimir Lenin who was made the Soviet icon. Thr hero of Soviet children was Pavel Morozov, a Komsomol boy who was said to have sacrificed himself in the fight for collectivization. The story involved reporting his parents to the authorities, this becoming the poster boy for the totalitarian socities of the 1930s. His parallel in NAZI Germany was Herbert Norkus whose life was the basis for the first film made by the NAZIs after they seized power in 1933. (The NAZIs and Soviet Communists are often seen as political opposites. It is interwsting to note how similar they were.) Some authors (Samuil Marshak, Agniya Barto and several of the "oberiuty") managed to adjust to the demands of Stalinism. New poets appaered (Sergey Mikhalkov, Yelena Blaginina, Zinaida Aleksandrova and Lev Kvitko). In a way they were rather creative in establishing a new genre of political verses and lyrical poems for nursery play. There were many authors who wrotyer classic tales envracing Soviet realism (Arkady Gaydar, Valentin Katayev, Venyamin Kaverin, and Ruvim Frayerman). There were some attemposts at fantasy and humorous literature. Other writers took the sager expedient od adapting foreign literatyre (Aleksey Tolstoy, Lazar Lagin and Aleksandr Volkov), a reflection of the literary sterility of Soviet literature during this period. [Hellman]

Stalin in 1939 signed a Non-Agression Pact with Hitler unleashing thge NAZIs to launch World War II with the invasion of Poland. Stalin with his new NAZI ally proceeded to lainch a seies of aggressions that rivaled Hitler (Poland, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithianiam, and Romania). Stalin had expected another protracted World War I struggle in the West, draing the power of bith te NAZIs and the Western democracies (Britain and France). Instead after the fall of France (June 1940), Stalin found himself facing the NAZIs, alone on the Continent. Hitler's goal from the beginning was lebensraum in the East. He launched Operation Barbarrosa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, yje most massive military campaign in human history (June 1941). For Hitler it was a war of anialation, unlike any war fought in Europe during modern times. German military and part-military formations were given irders to pursur a barbarous war of anialation. The Jews were the first to suffer. Hitler's ultimate target, however, was not just Stalin and Communist supporters, but the Russian people themselves which because of their Slavic origins were considered to be a lower order of mankind. This created one of the titanic struggles of all time, a fight for existence between two entire peoples. Soviet society was fundamentally affected by the World War II. Writers like other Sovie citizens participated in the war as soldiers or as correspondents. Arkady Gaydar was one of the casulties. Wrirts were expected to support the war effort and build the morale of the Soviet people. Ideologiacl thems were replaced by War-time of protecing mother Russia and appeals to Russian nationalism. Soviet writers (Valentin Katayev, Aleksandr Fadeyev) depicted children and youth asactually fighting the NAZIs as well as working on the home front. [Hellman] Those of is in the West may question this until we consider what the NAZIs had in mind for the occupied East after the War.

The Soviet inteligencia had hoped that the relaxation of ideological rigidity and ploce state purges would continur after the victory over the NAZIs. They were wrong. More Stalinist purges followed the World War II victories. Wrirts were not exempt. There was an ideolicalluy based campaign against "undesirable" writers (Chukovsky and others). The purpose of these campaigns wwere not really ideolgical not did the writers involved present a threat to Stalin. Rather it was pure terror. Every Soviet writr realized that it could have just as easily been him that was targetted. Hellman maintains, "The decade

after the war was to be the darkest in the history of Soviet Russian literature." [Hellman] Soviet children's literature was characterized by the "Theory of Conflictlessness" and the prtrayal of ideal characters without moral flaws. In this regard, Soviet realism was a far deoarture from realistic depictions. Writers to protect themselves eagerly competed to contributed to the "Stalin Cult". Imprtant themes in post-War children's literature included educational importance of physical labour (Aleksey Musatov, Susanna Georgiyevskaya,

and Nikolay Dubov). A interesting genre was the school story, but quite different from the well-known British school story. The Soviet school stories often involved a conflict between the class collective and a brave individualistically minded pupil (Valentina Oseyeva and Mariya Prilezhayeva). The Cold War was another popular theme (N. Kalma). There were several especilly importanr writers (Lyubov Voronkova, Anatoly Rybakov and the humorists Nikolay Nosov, and Yury Sotnik. Poerty is especially important is Russian literature, but during te post-War era was heavuky politicized (Sergey Mikhalkov). [Hellman]

Stalin died in 1953, but his spectre continued to haunt Soviet literature for decades.

The criticism of Stalinism at the XXth Party Congress by Nikita Khrushchev 1956 had an electric impact on Soviet literature, including children's literature. The resulting "Thaw" saw a new generation of writers willing to write creatively which provided shome inovative new themes and sttylistic approaches. and enriched literature both thematically and stylistically. Some wonderful new poets (Boris Zakhoder, Valentin Berestov, Emma Moshkovskaya, Roman Sef, Irina Tokmakova and Genrikh Sapgir) wrote for a new children's publishing house Detsky mir (The Children's World), which unfortunately did not last long. They developed folklore themes and children's rhymes. They harkened back to the avantgarde of the Golden Age in the 1920s. Writers began to realtically address the problems of childhood and adolescenr (Nikolay Dubov). Other issues that had been avoided in an effrt to depict the Soviet Unin as a worker's paradice were addresses, including orphans, divorce, and juvenile delinquency. Rgere were interesting works on psychological prose (Anatoly Aleksin, Yury Yakovlev, Rady Pogodin and Vadim Zheleznikov), adventure stories (Anatoly Rybakov), novels for girls (Lyubov Voronkova), humorous prose (Viktor Dragunsky, Viktor Golyavkin), fantasy and fairy tales (Yuri Druzhkov, Nikolay Nosov) and science fiction

(Arkady and Boris Strugatsky). World War II had involved enormous sacrifice an effort. Stories about the War took on almost mythical propotyions and the although the Stalin cult had been eliinated, the Lennin cult was still an important theme (Zoya Voskresenskaya, Mariya Prilezhayeva). Other political literature also continued to be important. [Hellman]

After Khrushchev was deposed in 1964, Soviet leadership passed to a series of elderly aparatchiks. While lacking the viciousness of Stalin, there common bond was fear of any change in the Soviet system erected by Stalin. The literay Thaw of the 1960s ended and ideological tests again became paramont in Soviet literature. Here there was probably more flexibiklity in children's literatute than adult literature. Even so, the creativity of the 1960s was a casualty. Hellman reports "some of the optimism and vitality was lost". Few important new writers appeared. Some writers did appear (Yury Korinets, Albert Likhanov, Vladimir Amlinsky and Vladislav Krapivin). Some works in fantasy and fairy tales(Eduard Uspensky and Sergey Kozlov) science fiction (Kir Bulychev) appeared. [Hellman]

Mikhail Gorbachov became Communist Party Chairman in 1986 and called for "perestroika" and "glasnost". The Eighth Writers' Congress in 1986 was the first official assessment of how to pursue the katest party dictates. The importance of children's literature had declined in the Soviet Union. An All-Union competition in 1987 for the best children's book resulted in few note worthy submissions. There were no exciting new names, and writers avoided topical, but possibly touchy issues. Hellman describes the state of Soviet children's literature, "In a situation in which the ideological monopoly of the party has been broken and the socialist ideals obscured, the role and content

of literature are once again being re-examined. The results of many decades' experience of ideological control and censorship in

children's literature are depressing. Shifting political trends have had a decisive influence on the contents of books for children, while the

dogma of socialist realism has impoverished their form. Talented writers have been hampered in their development, while ideologically

'sound' hacks have been allowed to dominate the field. Limited contact with foreign literature has added to the overall stagnation." [Hellman] The first real indication that Soviet writers were responsing to "perestroika" was a more accomodating attitude towards religion. Teligion had for years been a taboo topic, especially any favorable reference in youth publications. The journal Vesyolye kartinki (Funny Pictures), began to run Biblical tales in 1989 which at the time must have startled some parents. This began a re-evaluation of Russia's literary heritage, including pre-Revolutionary authors, that still continues today. [Hellman]

Hellman, Ben. Children's Books in Soviet Russia: From October Revolution 1917 to Perestroika 1986.

McGill University, Rare Books and Special Collections Division. "Children's books of the early Soviet era," 1999.

Navigate the HBC literary pages' Historical Clothing Web Site:

[Return to the main Main Soviet children's literary page]

[Return to the main Main literary page]

[Return to the main Main Russian page]

[Return to the main Main children's literary page]

[America]

[England]

[France]

[Greece]

Navigate the Boys' Historical Clothing Web Site:

[Introduction]

[Activities]

[Biographies]

[Chronology]

[Clothing styles]

[Countries]

[Bibliographies]

[Contributions]

[FAQs]

[Glossaries]

[Satellite sites]

[Tools]

[Boys' Clothing Home]