Genéral de Gaulle (France, 1890-1970)

"Whatever happens, the flame of French resistance must not and shall not die."

-- Charles de Gualle , June 18, 1940.

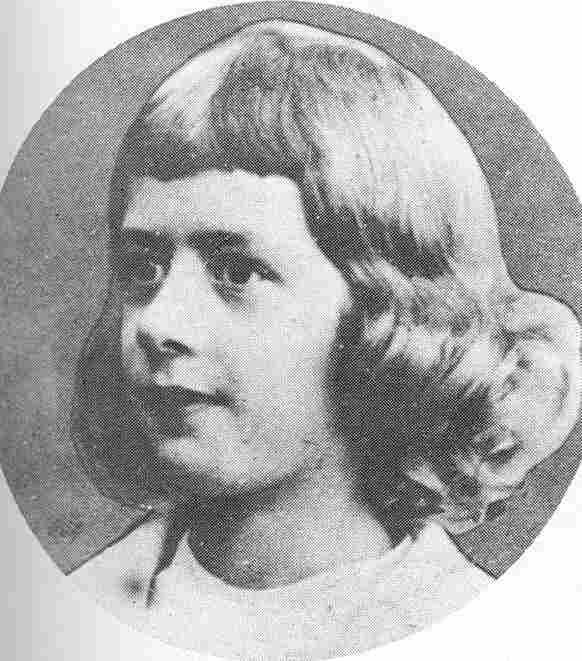

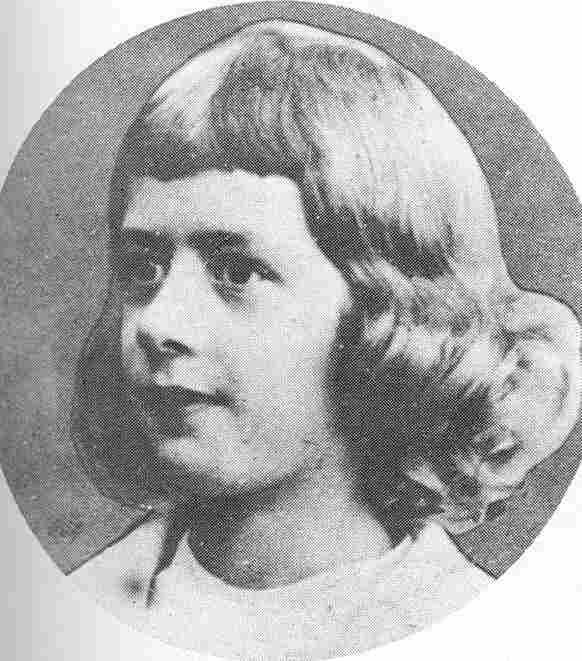

Figure 1.-- Charles had a spledid set of curls as a boy. I'm not sure when they were cut. He was 7 years old here which means the portrait was taken about 1897. We think ht he is wearing a white sailor suit. Some famous people are easy to spot as childern. I doubt if many people would recognize Charles here as the future general, soul of the French resistance to the NAZIs, and president.

|

|

General Charles de Gaulle is the most important French political leader of the 20th century. Many saw him during the dark years of German occupation as the savior of the French nation. His name today is averywhere in France and the former colonies (airport, streets, places, ect.). DeGualle as a junior officer had a gallant record from World War I. He commanded an armored division in the first year of World War II. He refused to surrender after the German invasion in 1940. He rejected the armistace and escapd to Britain where he organized the resistance to the Germans and the Vichy French Government which was collaborating with them. He formed the French National Committee which evolved into the Free French movemnent. He became convinced that his destiny and that of France were intertwined. He made inspired radio broadcasts to occupied France. DeGualle quarled with both Churchill and Roosevelt who did not recognize his Free French movement as the Goverment of France. After D-Day, however, his popularity helped himn to quickly organize a government in the liberated areas. A French reader writes, "Général de Gaulle was not very well understand by President Roosevelt and Primeminister Churchill. Genéral de Gaulle is still highly respected in France. One finds his name everywhere . He is for us the real France in his independance, shining through the world. He is the father of our nuclear force; the friendly Franco-German; and peace in the world. President Chirac admired Général de Gaulle. Still to day some anti-American French mentality is coming of this problem, but all the French are aware that the French-American friendly is for ever."

Parents

Charles grew up in a fervently patriotic and devoutly Catholic family middle-class family. His father was Henri de Gaulle, a schoolmaster. Henri taught philosophy and mathematics. He was a veteran of the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), in which Prussia/Germany delivered a humiliating defeat to the the French which most Europeans felt was he strongest power in Europe. This loss affecte de Gaulle's father, like many other French people. He was a patriot who fervently believed that the defeat had to be avenged and Alsace and Lorraine won back to France. His patriotism was passed to his children whom he groomed to aid in France's rebuilding the prestige of France. His mother was Jeanne Maillot. Both his parents immersed the children in French history. The family goes back centuries with a record of patriotism. Aa Chevalier de Gaulle helped defeat an invading English army at Vire (14th century). Jean de Gaulle is cited in the Battle of Agincourt (1415). Biographers report that an uncle, also named Charles de Gaulle, was also a major influence. He had written arespected book about the Celts--ancient people of northern Europe before the Germans and Slavs and the dominant population of what is now France when Caesar brought Gaul into the Roman Empire. He alled for union of the surviving Celtic peoples (Breton, Scots, Irish, and Welsh). De Gaulle as a young schoolbo wrote in his copybook a sentence from his uncle's book, which proved to foreshadow his future role: "In a camp, surprised by enemy attack under cover of night, where each man is fighting alone, in dark confusion, no one asks for the grade or rank of the man who lifts up the standard and makes the first call to rally for resistance."

Charles was born in Lille in the north near the Belgian border (1890). The family soon moved to Paris, but there were constant trips back to Lille to visit family. Some authors believe that this association with the north influenced Charles, giving him a sharper edge and more aware of the Germans. Charles was the third of five children in the family. He had an older brother Xavier (1887–1955) and sister Marie-Agnes (1889–1983), and two younger brothers, Jacques (1893–1946) and Pierre (1897–1959). He was repeatedly close to his youngest brother, Pierre. The two were so close in phsical appearance that presidential security personnel often saluted him by mistake when he visited his brother or or even when he came along on official visits. The children adored their father. He would take them for walks. These would always begin with, "Fall in by the door." Often they did not enjoy these walks, but their father would add stops at pastry shops or taverns to buy cheese and cider or beer. While in Paris, they might go to the Arctriomphe or to Napoleon's Tomb in the Invalides. There father had fought in the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71) during which Alsace-Loraine was lost. He would show the children where he fought at Le Bourget or Stains. [Lacouture, p. 8.] Charles appears to have been a difficult child. As a boy, his father was able to control Charles. His mother reportedly could not. His elder sister Marie-Angès knew him very well as she was often in the position of defending the younger children from him. She reports that their mother from an early age was able to exert virtually no authority over him. She recalls once when Charles was about 7 years old that Charles announced to Maman that he wanted to ride the pony. She refused telling him that he rode the previous day. Charles then announced, "Then I'm going to be naughty." He proceeded to toss his toys about, shoting, crying, and stamping his feet. Roosevelt and Churchill shurly would have agreed that he did no improve much with age. Charles was known to lock the bedroom door so mother coud not intervene and pound in Jacques and Pierre. His father was known to give him coins to be good and not bully the younger ones. Charles loved games, especially competitive ones. Some of the games the children played at home were: diablo, croquet, kites, ball games, blind man's bluff, and others. A favorite was war games with his toy soldiers. When the boys played with the soldiers, Charles always commanded the French trops. [Lacouture, pp. 6-8.]

Childhood Clothing

We have very little information about Charles' boyhood clothing. We see him wearing sailor suits. He also had long hair.

Education

The children's school master father was very serious anout academics. He insisted that the children study even during the holidays. Here Charles did his work, but often at school he did not. His elder brother Xavier was a better student and his father pushed Charles to be more diligent. Charles received a rigorous French education. He was taught first by the Christian Brothers. Then by the the Jesuits (Collège de l'Immaculée Conception, the Antoing--Belgium, and the Collège Stanislas). A 1900 portrait shows him wearing a large white Peter Pan collar which he wore to school. He was 10 years old at the time. At the time he was not yet especially tall. As a younger boy Charles did not apply himself. But under considerable pressure from his father he began to give more attention to his studies at about 14 years of age. [Lacouture, p. 9.] De Gaulle decided on a militry career and entered the prestigious French military academy Saint-Cyr (1909). He graduated from Saint Cyr (1912). He ranked near the top of his class, 13th among the grduating 210 cadets. Many of graduating class blieved that de Gaulle would make a great military leader.

World War I

After graduating from Saint Cyr, De Gualle joined an infantry regiment commanded by the then Col. Philippe Pétain. He quickly imoressed Pétain and other important officers with his intellifence. De Gualle as a junior officer had a gallant record from World War I. He fought courageosly in the Battle of Verdun, arguably the most important battle of the War. He was wouunded three times and captured by the Germans. He was a Prisoner of War (POW) for nearly 3 years. He attempted to escape five times, but never succeeded in escaping.

Inter-war Era

De Gualle during the inyer-war era actively persued his military career. He served on the French military commission to Poland and promoted to major was part of the French occupation force in the Rhineland (1927-29). It was at this time that he became increasingly concerned about Germany, even before Hitler and the NAZIs seized power. He also served with the Army in the Middke East. De Gualle taught at Sait Cyr and was selected for advanced training at the Ecole Supérieure de Guerre (French WAr College) (1923-25). Marshal Pétain appointed him to the staff of the Conseil Supérieur de la Guerre (French Supreme War Council). Afterv promotion to lieutenabt colonel, De Guale served on the Vonseil Supéieur de la Défense Council (National Defense Council). De Gualle began to write on military strategy. He persued a range of themes. His most important book was The Army of the Future in which he argued for a small professional army that was highly meganized. The was in sharp contrast to French defense policy which was the maintenance of a large conscript army and static defense behind the Maginot line. When De Gualle began trying to win political support he encountered problems with high army officials including Pétain who attempt to prevent De Gualle from publishing another book.

De Gualle was given command of a tank brigade in the Fifth Army when the War broke out and then given command of the Fourth Armormed Division. The French had many excellent tanks, but no radio communication. French armored doctrine was different than the Germans. The French used their tanks piece meal rather than forming massed armored formations. When the German blow came (May 10), the German Panzers were spectaularly successful while the French tanks played only a minor role. De Gualle had been appointed Undersecretary for Defence and was used by Primier Reynard to coordinate with the British Government in the desperate days when German Pazers were driving into the heart of France. He was in London when the Reynard fell from power and Pétain signed an armistice with the NAZIs. De Gualle refused to surrender. He rejected the armistace as well as the Pétain Vichy Goverment.

De Gualle was largely unknown unknown to the French people, but organized the Free French resistance to the Germans and the Vichy French Government which was colaborating with the Germans. He formed the French National Committee and fled to England. The Committe was to become the Free French movemnent. He became convinced that his destiny and that of France were intertwined. [Haskew] Despite the overwealming victory, DeGualle chose to fight. He made inspired radio broadcasts to occupied France. It was these speeches that made him a symbol of French resistance. De Gualle quarled with both Churchill and Roosevelt who did not recognize his Free French movement as the Goverment of France. The American and British Torch landings (November 1942) secured Algiers and because of continued disagreements with Churchill moved his headquarters to Algiers. Despite the differences, directed the Free French Forces and the underground in France. After D-Day, De Gualle's popularity helped him to quickly organize a government in the liberated areas. A French reader writes, "Général de Gaulle was not very well understand by President Roosevelt and Primeminister Churchill. Genéral de Gaulle is still highly respected in France. Oone finds his name everywhere . He is for us the real France in his independance, shining through the world. He is the father of our nuclear force; the friendly Franco-German; and peace in the world. President Chirac admired Général de Gaulle. Still to day some anti-American French mentality is coming of this problem, but all the French are aware that the French-American friendly is for ever."

French Provisional Governments

De Gualle headed two provisional governents. This is sometimes glossed over by historians, but in fact was of enormous importance. France on the eve of liberation was a time bomb. DeGualle understood this the Allies did not. The Communists were the stringest ellement in the Resistance and had a chance of seizing control, somrhing that would not occur in free elections. DeGualle had, however, a stormy relationship with Primeminister Churchill and President Roosevelt. The President in particular had no intention of setting him up as the head of thr Provisional Government. After D-Day, DeGualle moved to seize control of the liberated areas. He was litterally the only person who could have prevented the Communists from seizing control of large areas of the country, especially the all important Paris. Again the Allies did not understand the importance of Paris. Eisenhower understandingly thinking militarily planned to bypass Paris to better pursue the retreating Germans. DeGualle relaized that if the Allies did not enter Paris, the Communists would seize control and another Commune might result. (The Commune was the 1870 seizure of Paris by leftist parties requiring the Third Republic to begoin by a bloody and destructive campaign to regain control of the capital.) French histoy is intricatly tied to the history of Paris more than any other country's history is tied to their capital. DeGualle understood this and eventually convinced Eisenhower to relieve the city which had risen up against the Germans. The Free French and American troops liberating the city combined with DeGualle's appearance forestalled a Comminist takeover. Had this not occurred, France may well have suffered a debilitating civil war like the one which occurred in Greece. De Gualle resigned over a minor matter (1946). Had his career ended here, DeGualle would have been a military and politucal figure of great importance, But of course it did not end here.

Rally of the French People (RPE)

He later formed a politival party, the Rally of the French People (RPE). He opposed the Fourth Republic seeing in it many of the weaknesses of the Third Republic. De Gualle eventually abandoned the RPE.

Algeria

France after World war II was liberted, but a weakened nation with the economy in shambels. A after the departure of DeGualle, plitically unstabe; with one short lived government following another. The one constant in the steady streanm of governments was a commitment to hold on to France's colonial Empire. The Viet Cong in Viet Nam fought the Japanese and refused to accept continued French rule. This lead to the disatrous First Vietnam War. France was soon sinking a substantial portion of its national budget into a war against the Viet Cong. This was a commitment that the battered French economy could not afford. The War finally ended when the French Army capitulated at Dien Bien Phu (1953). Just as military operations in Viet Nam ended, another colonial war began to develop--in Algeria. France was prepared to compromise in Tunisia and Morocco. Algeria was another matter. France saw Algeria as an integral part of the country. Large numbers of Frenchmen had setteled in Algeria--the pier noir. Further complicating the situation was the growing feeling that political leaders had sold them out, both in 1940 and again in 1953. They saw this about to happen again. France was veeering toward civil war. DeGualle returned at this time and his prestige overted civil war, but with the cost of separung France from Algeria.

Fifth Republic

It was the crisis in Algeria that brought De Gualle back to power. The war in Algeria brought France close to civil war. In the crisis, France again turned to De Gualle. He was was elected president (1958). He ended the long festering war in Algerian, recognizing Algerian indeoendence. He proceeded to grant autonomy to more than a dozen colonial possessions. [Haskew} The centerpiece of Guallist policy was strong support for the the Franco-German relationship which is the core of modern Europe. And it is DeGualle's constitution that has

provided France a stable government. And DeGualle an Pompidu support for free markets and capitalism was a major reason for the prosperity that France achieved. DeCualle served as president for 10 years amid some controversy. Leftists parties were very critical of his leadership. He irritated the Americans by leaving NATO and attempting to negotiate a favorable reltionship with the Soviets. Less admirable is trying to cut a separate deal with the Soviets rather than participating in a unified Western response.

Cpt. de Gaulle after valliant service in World War I met Yvonne Vendroux at a ball. He had just reyurned from a mission in Poland. There was an immediate connection. They married married in the church of Notre-Dame-de-Calais (1921). The new couple established a home at La Boisserie, in Colombey-les-Deux-Églises. Their marriage was It was a life-long union. They had three children: Philippe (1921), Élisabeth (1924–2013) who married General Alain de Boissieu, and Anne (1928–1948). Anne had Down's syndrome and died of pneumonia when she wa only 20 years old. De Gaulle perhaps because if her disability was devoted to Anne. A neigbor in Colombey recalls how he used to walk with her hand-in-hand around the grounds of their home. He would tenderly caressed her and they would talk about the things she could understood. De Gualle and his wife were soul mates. Like him, she was a devoted, conservative Catholic. As De Gualle became a public figure, after the War she campaigned against prostitution, the sale of pornography in newsstands and the televised display of nudity and sex. The French began calling her "Tante (Aunty) Yvonne." She pestered her husband who at the time was the oresident to outlaw the miniskirt. It was alosing effort among fassionable young French women. We note an imge of two grandsons in 1962. The family was interested in politics. One of his grandsons, named Charles in his honor. He became a predictably Gulist member of the European Parliament (1994 - 2004), but switched to the National Front. This caused a scandal within the family and was sharply criticized him publically in letters and newspaper interviews. One family member commented, "It was like hearing the pope had converted to Islam". ['La famille ...'] Another grandson, Jean de Gaulle, served in the French parliament until his retirement (2007).

Quebec (1967)

What may be the height of ingraditude is what he did in Canada. You may not know that French Canadians

resisted serving in both World War I and II. As a result, most of the Canadian soldiers that fought with France in World War I and helped liberate France in World War II were English-speaking Canadians and not French Canadians. To then after the War go to Canada and go on about Quebec Libre is the height of ingraditude.

A French reader writes, "First no one in France, nor any French Government government showed

any ingratitude for all the American, English, Canadian,and other soldiers wich rescued France in 1944. All these men who died on the earth of France are present in our conscience. But in the 1960s you have to remember about

the precarious balance of the world with the West and Eastern blocs. President Charles de Gaulle visited Quebec in 1967 invited by Quebec Prime Minister Daniel Johnson. President DeFualle enraged Canadian federal authorities when in Montreal, in front of a crowd of more than 100,000 people, he punctuated his speech by resounding: 'Vive Montreal, Vive le Québec, Vive le Québec libre!', greeted by a general ovation. That started of course a crisis with the Canadian government which was under the Anglo-Saxons banner. [HBC agrees with this basic statement with the exception of "under the Anglo-Saxon banner". Canada had a demoratically elected government and the Canadian Primeminister was in fact a French Canadiam.] The relations between France and Canada will be marked a long time by this speech. President de Gaulle said about Prime Minister Trudeau, ' We French have any concession, nor even no kindness, to make with Mr. Trudeau, who shows much adversary of the French thing in Canada.' The aim of De Gaulle wasn’t to cause a 'clash' between Quebec and the Canada govement but rather to "cheer up" the French-minority in of Canada beeing face to their Anglo-Saxon neighbours. He declared elsewhere in the tread of this visit in Quebec, “I saved to them 30 years”. This declaration was felt as unjust by the anglophone Canadians who had supported free France during the World War II. French Canadians were much less supportive of the War and many opposed the draft. There concern was more with independence from Britain. They were thus less enthusiastic in taking part in the war effort and the crucial liberation of France.

It is difficult assess people's motives. I have never seen any thing DeGualle himself wrote to explain what he did, but my knoledge of the whole event is limited.

I certainly do not think he MEANT to derepect the Canadians (mostly English speaking) that fought for France in two World Wars. Nor do I even know that he realized that few French Canadians participated in the effort. (There was a great deal of resistance to the War in Qubec and opposituoin to the draft. In the end French Canadian draftees were not sent to Europe.) But whatever DeGualle's intentions, the Cananadian servicemen who helped liberate France perceived it as disreceot for their service and their ciyntry's role in liberating France.

There would have been no problem sying "Vive Quebec", but "Vive Quebec Libre" is a very different matter. Think for a minute, what would DeGualle would have said if President Eisenhower went to Algiers in 1959 and delivered a speech ended with "Vive Algire libre" or how the Spanish would feel if he went to Bilbao and proclaimed "Vive Basque libre".

I have always thought that DeGualle did not give much thought to what he said, but rather got carried away with the moment. But I have no way of really knowing that. It may well be that it was a carefully considered step, part of DeGualle's overall view of the need to parlay Anglo-Saxon dominance in the world.

The May 1968 Paris student riots had a fundamental impact on French and Wider European society. A part of the impact was on fashion. Just as the War in Viet Nam was having a major imact on American society. The Paris Student Riots are now seen as a major watershead event in France. As Charles Dickens put it about an earlier French Revolution, "They were the best of times, they were the worst of times. Surely the virtual open warfare in the strrets of Paris during those May days shattered the old order in France more surely than any popular uprising since the Great revolution of 1789. Students and police clashed around burning cars and barricades. Half the French work force struck in solidarity-freezing the gears of a society which at the time was enjoying record prosperity. As a result, the mighty Charles de Gaulle fell from what had seemed a presidency for life. Other popular movements were underway that Spring. The U.S. anti-War movement, the Prague Spring, and violence on campuses from Japan to Italy to Mexico. A new world order seemed at hand. The events are relatively unrecognized in America as we were in the grips of our own national upheaval. DeGualle's last great gift to his country was preventing the 1968 Paris riots from spiraling out of control.

Final Years

French Assessment

General Charles de Gaulle is the most important French political leader of the 20th century. His name today is everywhere in France and the former colonies

(airport, streets, places, ect.). A French reader writes, "Général de Gaulle was not very well understand by President Roosevelt and Primeminister Churchill. Genéral de Gaulle is still highly respected in France. Oone finds his name everywhere . He is for us the real France in his independance, shining through the world. He is the father of our nuclear force; the friendly Franco-German; and peace in the world. President Chirac admired Général de Gaulle.

Still to day some anti-American French mentality is coming of this problem, but all the French are aware that the French-American friendly is for ever."

Sources

Haskew, Michael E. (2011), 224p.

Lacouture, Jean. DeGaulle: The Rebel 1890-44 (WW Norton: New York, 1990), 615p.

"La famille qui a dit non," Le Point (July 16, 1999).

HBC

Navigate related Boys' Historical Clothing Web Site pages:

[Return to the Main biographies D-E page]

[Return to the Main Vichy page]

[Return to the Main World War II biographies page]

[Hair styles]

[Collar bows]

[Dresses]

[Tunic]

[Knee breaches]

[Kilts]

[Fauntleroy suits]

[Fauntleroy dresses]

[Sailor dresses]

[Pinafores]

[Smocks]

[Pantalettes]

Navigate the Boys' Historical Clothing Web Site:

[Introduction]

[Activities]

[Biographies]

[Chronology]

[Clothing styles]

[Countries]

[Bibliographies]

[Contributions]

[FAQs]

[Glossaries]

[Images]

[Links]

[Registration]

[Tools]

[Boys' Clothing Home]

Created: 7:19 PM 6/30/2004

Last updated: 2:30 AM 11/9/2016